April was the first negative month of the year, with the MSCI World Index falling 3.85% following an excellent Q1.

Stubbornly high inflation readings weighed on markets as the prospect of cuts to interest rates weakened, with most now expecting that they will not happen until the back end of the year, if at all, during 2024.

Annual CPI rose again in March, up to 3.5% from February’s 3.2%. The cost of shelter has increased by 5.7% in the last year, which accounts for approximately one-third of the CPI weighting. Core inflation, excluding food and energy prices, rose by 3.7% annually in Q1. The personal consumption expenditures price index saw its biggest gain in a year, growing at an annualised rate of 3.4% in Q1, compared to 1.8% in Q4. Whichever inflation metric you use, or however you try to interpret the data, it remains the case that inflation is still stubbornly high.

Whilst inflation remains high, the US economy and labour market remain hot, with a further 303,000 jobs created in March, far above expectations of 200,000. Retail sales also rose by a higher-than-expected 0.7% in March, and the February figure was revised upwards from 0.6% to 0.9%. The IMF has also predicted GDP expansion in America this year to be 2.7%. All this data suggests that high interest rates are not slowing down economic activity enough to curb inflation, hence the likelihood of a delay to rate cuts.

Investors priced in the first rate cut for September — pushed back from June — on the back of the news, causing the stock market to fall. The Dow Jones had its worst day since January, and 476 out of the S&P 500 companies traded in the negative.

Markets were further shaken the following week when Jerome Powell, chair of the Fed, said that it would “likely take longer than expected” to lower interest rates due to inflation remaining high. The Fed’s preferred inflation measure, core PCE, increased 2.8% in March from a year ago, the same reading as for February. Powell’s comments caused both the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq to fall for a sixth consecutive session, their worst run since October 2022.

Bond markets are also repricing, with their expectations now set at one-and-a-half interest rate cuts by the end of the year, compared to six at the start of 2024.

Tensions in the Middle East are also adding to the inflation issue (on a global scale as well as just in America). Direct strikes between Israel and Iran increased oil prices above $90 per barrel, and if they stay elevated, it will feed back into high inflation numbers.

The strikes between Israel and Iran did not escalate. Iran indicated that it would not respond to Israel’s retaliatory attack, and markets assessed that both sides wanted to show strength without causing wider harm. Oil fell back to $86 per barrel following this. OPEC+ has the capacity to increase production if necessary, but markets will watch carefully, and geopolitical risk is likely to be priced in for some time yet.

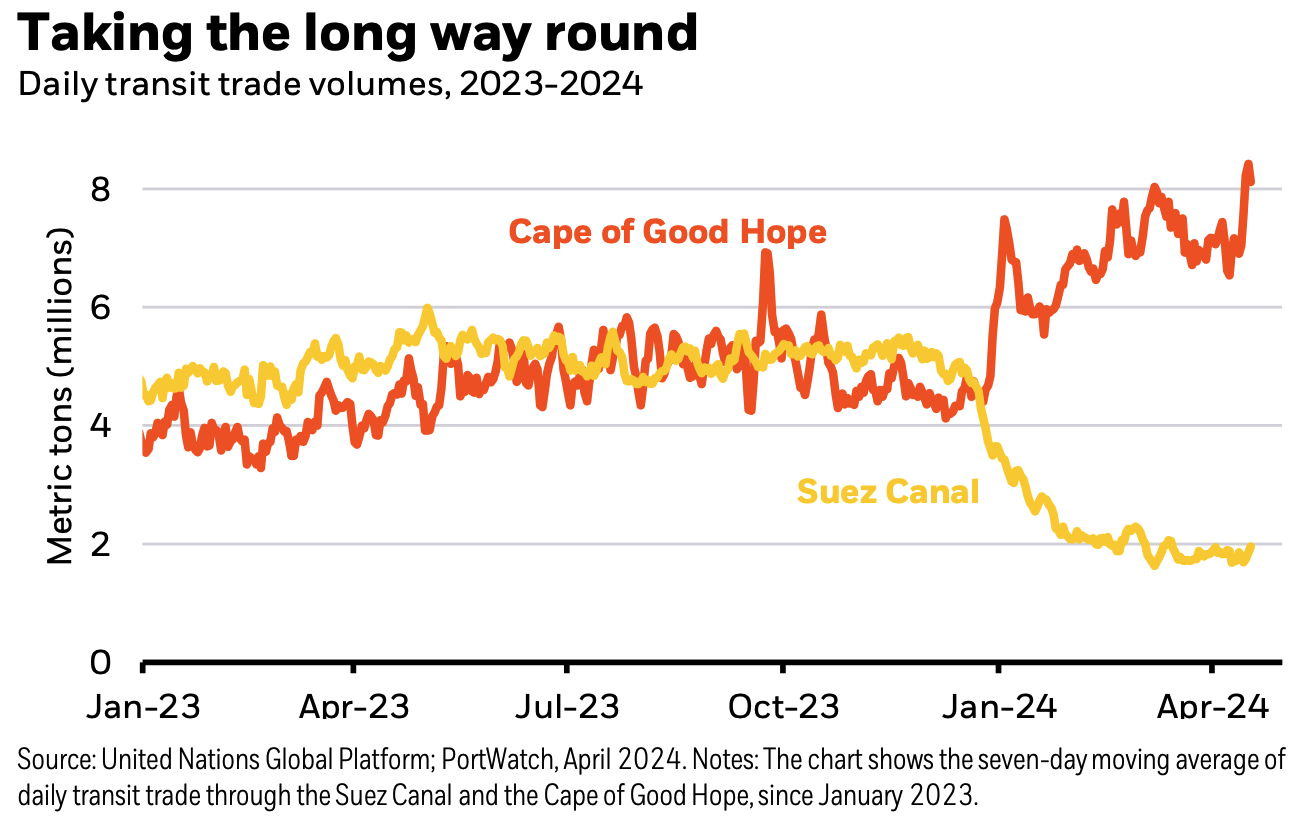

Flights were diverted to avoid Jordanian airspace – over which the missiles were flying – and shipping traffic is lower through the Suez Canal, as Iranian proxy attacks by Houthi rebels in Yemen cause companies to want to avoid their ships travelling through the Red Sea.

Shipping is being heavily diverted to travel around the Cape of Good Hope, with increased travel time and fuel usage increasing costs and driving goods inflation. Since the attacks, shipping costs from China have risen by 75% from the end of 2023. Supply constraints such as this were key drivers of inflation in the early stages of the post-pandemic rebound at the end of 2021. When China was in lockdown, shipping out of Shanghai became much more costly, and the inflation of goods skyrocketed. Now, it is not Chinese workers being locked down that is the issue; it is the need for ships to travel further and businesses, therefore, to spend more money to get the same goods across the world.

The US has been looking to reduce its economic dependence on China, which may lessen the impact there. However, it will take time to fully diversify its source of goods, and global inflation may still suffer from the current impact on shipping.

America overtook China as the largest destination for Taiwanese exports, with the territory’s exports to the US rising 65.7% from a year ago. Exports to China grew by just 6%.

The Biden administration is trying to reduce economic dependence on China. In a further boost to Taiwan, it announced $6.6 billion of direct funding to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) to help build facilities in Phoenix, Arizona, to make the world’s most advanced semiconductors. TSMC is the largest contract chipmaker in the world and is making the largest foreign direct investment in a “greenfield” project, increasing its investment in Arizona to $65 billion.

Separately, the US gave South Korean firm Samsung a $6.4 billion subsidy to build semiconductor facilities in Texas, where the chipmaker already has some presence. $40 billion worth of investment has already been made in constructing and upgrading chip factories, a packaging plant, and a research centre.

Samsung also overtook Apple as the world’s biggest phone maker in Q1, shipping over 60 million smartphones compared to Apple’s 50 million.

Manufacturing activity in China grew in March for the first time in six months, with manufacturing PMI indicating economic growth compared to contraction in February. This performance was not replicated in other Asian economies, with Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan seeing factory activity slowdown during March.

The Chinese economy grew 5.3% annualised in Q1, which was higher than expected. Most of the growth came in January and February, while retail sales struggled in March. The ongoing issues in the country’s property market saw a sharp fall in cement output.

The Japanese yen fell to its lowest value against the US dollar since 1990. With interest rates so much lower from the BoJ compared to other central banks, the yen has become a less valuable currency to hold.

The Japanese Ministry of Finance made overtures about intervening in currency markets to support the yen.

Figures for the UK’s public finances made poor reading, with borrowing of £6.6 billion in March much higher than the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) had predicted. This is economically and politically poor, with a general election set for later this year.

The implications of these figures mean that either taxes will rise or spending cuts will be introduced after the election, meaning that a new government will dictate long-term fiscal policy. This causes problems for opposition parties, who do not want to commit to commitments now or risk losing votes in the election.

The UK already has a high debt, in relative terms, taken on when interest rates were low. Refinancing the debt as time goes on means it will incur higher interest rates and take up more national income to pay off. The UK currently spends an estimated 3.2% of national income on its debts, so any growth in this will not be good for the economy.